“You’re not dumb for owning your sexuality or trusting someone you love.”

A public speaker, author and ethical hacker for Orange Cyberdefense, Mia Landsem tells us about her unintended career path to fame. She also shares her experience with digital image-based sexual abuse and explains why she is helping other victims of this growing crime to fight for justice.

What is an ethical hacker?

Basically, it’s legal hacking. When people hear the word ‘hacking’, they assume it’s illegal, but we’re paid to hack companies. We’re actually an important part of cybersecurity, for new computer systems, web applications, endpoints, or anything that involves personal information online. We test for security weaknesses – anything the bad guys will be looking for – then, we write a report and suggest system changes that need to be made.

Ethical hackers, which are also known as penetration testers or pentesters, are different to hacktivists, but I’m not a hacktivist. I don’t do illegal hacking.

What do you love about your job at Orange Cyberdefense?

When I started working at Orange Cyberdefense, which launched in Norway three years ago after acquiring SecureLink, I was the third member on the ethical hacking team. Now, there are 12 of us, and we’ve grown from 30 employees to 90. It’s fun, even though it’s also a difficult job. I get to break into computer systems and manipulate people to get information – almost like a super-spy!

It might seem like a website or web application security test will be the same every time, but I always see new stuff. And when we get an exciting assignment, we have so much fun talking about it. We’re basically getting paid to do something that’s illegal in other circumstances – and it’s well paid, although that’s not what drives me.

Why did you start a bachelor’s degree in sports science psychology and coaching?

I was on the Norwegian junior national team in Taekwondo and became a regional and double Nordic champion, winning several medals and prizes in national and international ranking tournaments. The Norwegian School of Sports Sciences had ten spaces for top athletes on its bachelor’s degree in sports science psychology and coaching, and I was one of the athletes selected. I wasn’t really aiming to become a sports coach. My big dream was to go to Oslo, where the national team is based, and aim for the Olympics. I had no thought in my head that I would ever work with IT.

How did you get into IT?

I love gaming, as well as sport and martial arts. In 2014, I was on a TV show called Gamer, where I talked about how I wanted to use the techniques I use in martial arts to be better at gaming and vice versa. It’s been found that professional gamers have better reaction skills than professional athletes. At the end of my second year at the Norwegian School of Sports Sciences, I hurt my knee and couldn’t walk. It was a very difficult period in my life because I needed surgery, I was on crutches for six months, and I’d gone through a really bad breakup with my then boyfriend and had to find a new place to live. It was also then that I reported a previous ex for digital image-based sexual abuse.

I also had a puppy to look after, Zelda. She’s everything to me, so, I quit school in my third year and started researching distance learning schools so that I could stay at home with her. There was an online school with a campus in Oslo that did a two-year course in network and IT security, which I chose because I didn’t have the maths qualification required to do a bachelor’s degree, and because I could switch to the campus when Zelda was old enough to be alone for several hours.

How did you become an ethical hacker?

My original plan was to do a bachelor’s in cybersecurity or digital forensics and work for the police. In Norway, you can skip the maths requirement for a bachelor’s degree if you’re 25 or older and have work experience. I was going to be 23 when I finished my network and IT security course, so I thought I’d find an IT support role for two years and then jump onto the bachelor’s degree. But I didn’t really have a solid plan. I was really busy, travelling, doing talks about digital image-based abuse, and I was diagnosed with ADHD.

The lockdown brought on by the COVID-19 pandemic turned out to be an opportune moment for me. I loved the isolation, and it gave me the headspace to think about what I wanted to do. At one point, I asked people in an IT security group on Facebook if they knew of any jobs I could do with two years’ IT experience, and someone recommended ethical hacking.

I’d only done a four-week course in digital forensics and a four-week course in hacking, but I ended up getting interviews with a number of companies. Part of the reason I chose Orange Cyberdefense was because it supports the campaigning I do outside of work.

Would you say that not having a life plan has worked well for you?

Lots of people ask me how I do the stuff I do and how I knew what to do to get to where I am, but I didn’t know what to do. When I moved out of my mum’s house, I couldn’t even wash my clothes! Stuff just happened. I followed my heart. There was never any big plan. I just needed a student loan to continue living in Oslo and be with my puppy.

Can you give some examples of the things you say to young people in your talks about internet awareness?

I talk about everything, from online security to identity theft, digital stalking, porn and image abuse. I talk about all the heavy stuff and what young people should do if something bad happens to them. I tell them to talk to professionals. But I don’t just talk to young people. I also talk to parents about how they can discuss online security with their children. Not all parents have grown up with technology in the same way as their children, so there’s a lot to learn about parental controls and protecting children when they enter the digital world.

I’ve also done talks for the police, foster parents, childcare services and women’s crisis centres. And I’ve produced a video for children and adults who use sign language.

Where does your passion for these issues come from?

If you asked my first-grade teachers, they would say I don’t like unfairness. It’s true. I really care about what’s right and wrong. I was bullied when I was younger, and I thought it was unfair, so I always used to step in if something bad was happening to someone else. I didn’t ask for help when I was having problems. I guess I’ve become the help I wish I’d asked for, the help I needed but didn’t get.

How did you manage to stay so strong when you had your experience with digital image-based sexual abuse?

The picture of me having sex was taken when I was 17. My boyfriend at the time shared it a couple of months before my 18th birthday, and then it turned up everywhere. It was horrible. I didn’t want to live anymore. I didn’t ask anyone for help, even though everyone knew about it, apart from the adults, of course.

I actually have no idea how I survived. I became really anxious and depressed, but I don’t really remember much from that time. I was helping people before my picture got out, so I already knew about the forums and websites where images are shared without consent. And then it happened to me. I found my own picture on one of those forums. My ex had sent it to a friend of mine who sent it to two others, and then it ended up being shared among the gaming community.

How common is digital image-based sexual abuse?

Very common. People aren’t scared to do it and it’s horrible. I don’t understand why they’re doing it. It used to only happen to celebrities but now it’s happening to everyone.

Is it partly that teenagers do not understand the consequences of what they are doing when they share an image like this?

If this was six years ago, I’d believe that, but most teenagers in Norway know who I am and what I do. I’ve done 500 talks in schools. I’ve been on TV. We talk about this. It’s in the schoolbooks now. ‘I didn’t know’ isn’t an excuse. People are hiding their IP addresses and using false accounts and names. Why would they hide that information if they didn’t know what they’re doing is wrong?

How much support is there for victims of image-based abuse?

None. It’s non-existent. The police might look at your case but most of the time they close it after about six months because they don’t have the resources to prioritise it. It’s really sad.

What advice do you have for young people who become victims?

Talk to someone, get as much evidence as you can and file a report with the police. Even though a lot of cases get thrown out, if other people start to report abuse from the same person, then it will be taken seriously. It also gives us an indication of the number of people reporting this type of abuse.

People always think they’re so dumb for letting this happen and don’t want to tell anyone, or for me to tell anyone. You’re not dumb for owning your sexuality and you’re not dumb for trusting someone you love. The one who is dumb and to blame is the abuser.

What can we as individuals do to help?

We have to shift the blame away from the victim. The problem is always the abuser, not the victim. Lots of people say that the victim shouldn’t have allowed their photo to be taken. You can see comments like that on social media. When abusers hear comments like that, it justifies their actions – “it’s their fault, not mine ”.

I often say to parents that even if you tell your kid to not let their boyfriend or girlfriend take pictures of them naked, they’re going to do it anyway. And if you’re one of those parents commenting on Facebook about how people shouldn’t let this happen to them, and your kids see it, you’re going to be the last person they come to for help.

What you can do is explain what might happen if a picture gets taken, then they’ll start thinking for themselves and might not want to take the risk. But if they do, and something happens, you want to be there to support them, not tell them they shouldn’t have done it in the first place.

Connect with Mia

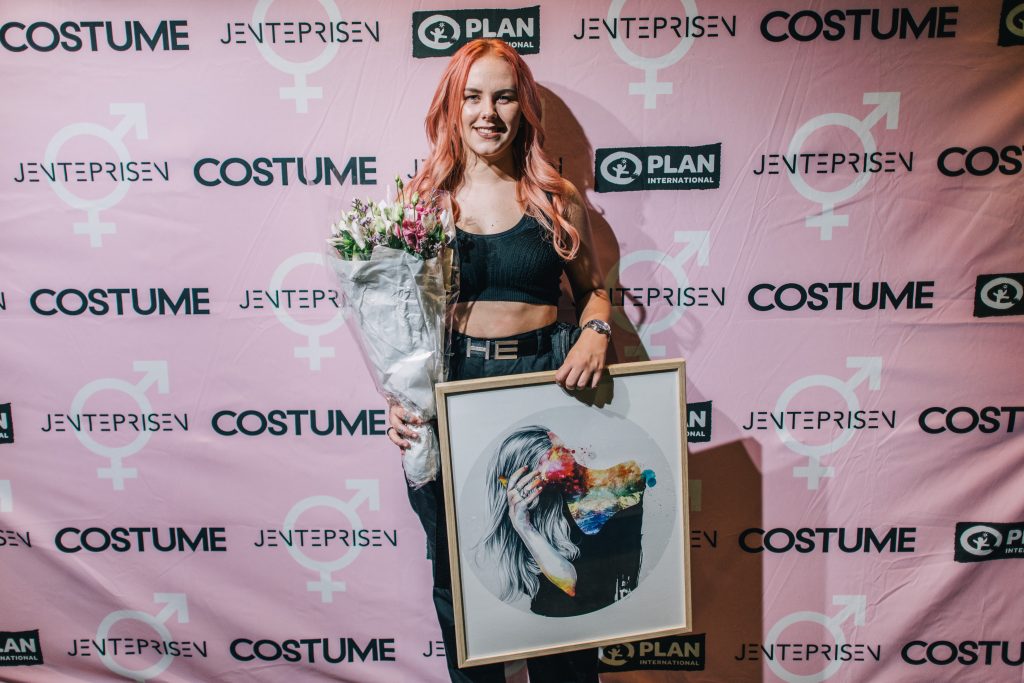

As well as working as an ethical hacker/pentester for Orange Cyberdefense, Mia speaks publicly about the dangers of the internet and how to keep safe. In 2020, she published a book about online safety for children, and in 2021, she was shortlisted for the Cybersecurity Woman of the Year award. Mia’s work on digital image-based sexual abuse has also earned her a number of awards.

About image-based sexual abuse

Image-based sexual abuse happens when someone shares sexually explicit images or videos of another person without their consent. Often, the aim is to cause that person distress or harm. Sometimes referred to as ‘revenge porn’, image-based sexual abuse is a criminal offence.

As Mia says, if you have experienced image-based sexual abuse it is important to remember that you are not to blame. Talk to people you trust and report the crime to the police. For support and more information, visit:

www.victimsupport.org.uk/crime-info/types-crime/cyber-crime/image-based-sexual-abuse