Computer Science was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: A historical perspective

November 26, 2021 at 10:00 am 23 comments

I gave four keynote talks in the last two months, at SIGITE, Models 2021 Educators’ Symposium, VL/HCC, and CSERC. I’m honored to be invited to them, but I do suspect that four keynotes in six weeks suggest some “personal issues” in planning and saying “No.” Some of these were recorded, but I don’t believe that any of them are publicly available

The keynotes had a similar structure and themes. (A lot easier than four completely different keynotes!) My activities in computing education these days are organized around two main projects:

- Defining computing education for undergraduates in the University of Michigan’s College of Literature, Science, and Arts (see earlier blog post referencing this effort);

- Participatory design of Teaspoon languages (mentioned most recently in this blog post).

My goal was to put both of these efforts in a historical context. My argument is that computer science was originally invented to be taught to everyone, but not for economic advantage. I see the LSA effort and our Teaspoon languages connected to the original goals for computer science. The talks were similar to my SIGCSE 2019 keynote (blog post about that talk here, and video version here), but puts some of the early history in a different perspective. I’m not going to go into the LSA Computing Education effort or Teaspoon languages here. I’m writing this up because I hope that it’s a perspective on the early history that might be useful to others.

I start out with C.P. Snow.

My PhD advisor, Elliot Soloway, would have all of his students read this book, “The Two Cultures.” Snow was a scientist who bemoaned the split between science and humanities in Western culture. Snow mostly blamed the humanities. That wasn’t Elliot’s point for having us read his book. Elliot wanted us to think about “Who could use what we have to teach, but might not even enter our classroom?”

This is George Forsythe. Donald Knuth claims that George Forthye first published the term “computer science” in a paper in the Journal of Engineering Education in 1961. Forsythe argued (in a 1968 article) that the most valuable parts of a scientific or technical education were facility with natural language, mathematics, and computer science.

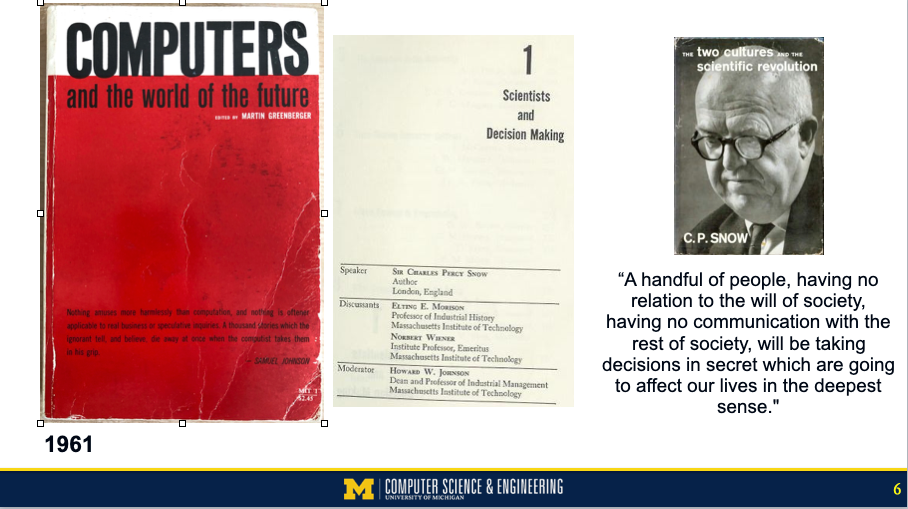

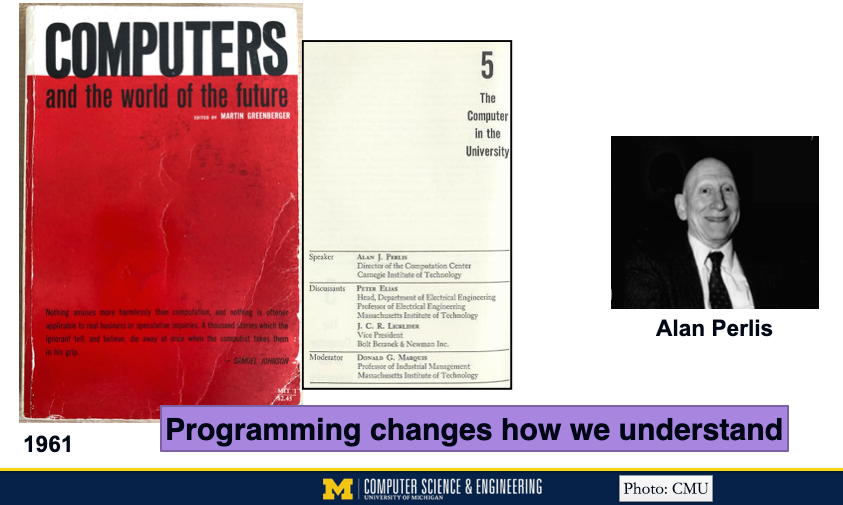

In 1961, the MIT Sloan School held a symposium on “Computers and the World of the Future.” It was an amazing event. Attendees included Gene Amdahl, John McCarthy, Alan Newell, and Grace Hopper. Martin Greenberger’s book in 1962 included transcripts of all the lectures and all the discussants’ comments.

C.P. Snow’s chapter (with Norbert Wiener of Cybernetics as discussant) predicted a world where software would rule our lives, but the people who wrote the software would be outside the democratic process. He wrote, “A handful of people, having no relation to the will of society, having no communication with the rest of society, will be taking decisions in secret which are going to affect our lives in the deepest sense.” He argued that everyone needed to learn about computer science, in order to have democratic control of these processes.

In 1967, Turing laureate Peter Naur made a similar argument (quoting from Michael Caspersen’s paper): “Once informatics has become well established in general education, the mystery surrounding computers in many people’s perceptions will vanish. This must be regarded as perhaps the most important reason for promoting the understanding of informatics. This is a necessary condition for humankind’s supremacy over computers and for ensuring that their use do not become a matter for a small group of experts, but become a usual democratic matter, and thus through the democratic system will lie where it should, with all of us.” The Danish computing curriculum explicitly includes informing students about the risks of technology in society.

Alan Perlis (first ACM Turing Award laureate) made a different argument in his chapter. He suggested that everyone at University should learn to program because it changes how we understand everything else. He argued that you can’t think about integral calculus the same after you learn about computational iteration. He described efforts at Carnegie Tech to build economics models and learn through simulating them. He was foreshadowing modern computational science, and in particular, computational social science.

Perlis’s discussants include J.C.R. Licklider, grandfather of the Internet, and Peter Elias. Michael Mateas has written a fascinating analysis of their discussion (see paper here) which he uses to contextualize his work on teaching computation as an expressive medium.

In 1967, Perlis with Herb Simon and Alan Newell published a definition for computer science in the journal Science. They said that CS was “the study of computers and all the phenomena surrounding them.” I love that definition, but it’s too broad for many computer scientists. I think most people would accept that as a definition for “computing” as a field of study.

Then, we fast forward to 2016 when then-President Obama announced the goal of “CS for All.” He proposed:

Computer science (CS) is a “new basic” skill necessary for economic opportunity and social mobility.

I completely buy the necessity part and the basic skill part, and it’s true that CS can provide economic opportunity and social mobility. But that’s not what Perlis, Simon, Newell, Snow, and Forsythe were arguing for. They were proposing “CS for All” decades before Silicon Valley. There is value in learning computer science that is older and more broadly applicable than the economic benefits.

The first name that many think of when talking about teaching computing to everyone is Seymour Papert. Seymour believed, like Alan Perlis, “that children can learn to program and learning to program can affect the way that they learn everything else.”

The picture in the lower right of this slide is important. On the right is Gary Stager, who kindly shared this picture with me. On the left is Wally Feurzeig who implemented the programming language Logo with Danny Bobrow, when Seymour was a consultant to their group at BBN. In the center is Cynthia Solomon who collaborated with Seymour on the invention of the Turtle (originally a robot, seen at the top) and the development of Logo curriculum.

Cynthia was the lead author of a recent paper describing the history of Logo (see link here), which included the example of early Logo use on the upper right of this slide, which generates random sentences. Logo is named for the Greek word logos for “word.” The first examples of Logo were about manipulating natural language. Logo has always been used as an expressive medium (music, graphics, storytelling, and animation), as well as for learning mathematics (see the great book Turtle Geometry).

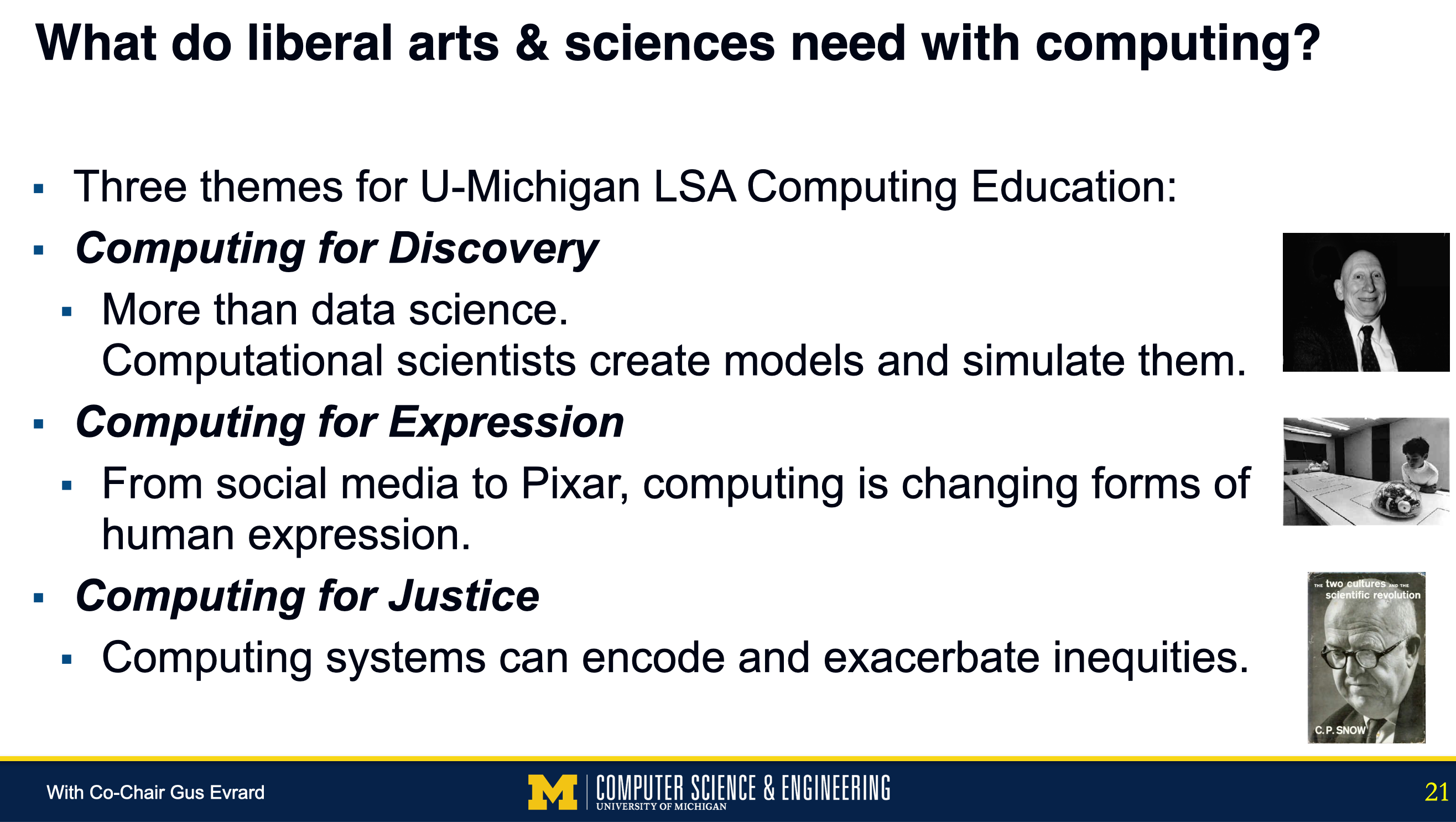

This is the context in which I think about the work with the LSA Computing Education Task Force. Our question was: At an R1 University with a Computer Science & Engineering undergraduate degree and an undergraduate BS in Information (with tracks in information analysis and user experience (UX) design), what else might undergraduates need? What are the purposes for computing that are broader and older than the economic advantages of professional software development? We ended up defining three themes of what LSA faculty do with computing and what they want their students to know:

- Computing for Discovery – LSA computational scientists create models and simulate them (not just analyze data that already exists), just as Alan Perlis suggested in 1961.

- Computing for Expression – Computing has created new ways for humans to express themselves, which is important to study and to use to explore, invent, and create new forms of expression, as the Logo community did starting in the 1960’s.

- Computing for Justice – LSA scholars investigate how computing systems can encode and exacerbate inequities, which requires some understand of computing, just as C.P. Snow talked about in 1961.

We develop our Teaspoon languages to meet the needs of teachers in teaching non-CS and even non-STEM classes. We argue that there are computing education learning objectives that we address with Teaspoon languages, even if they don’t include common languages features like for, while, and if statements. A common argument against our work in Teaspoon languages is that we’re undertaking a Sisyphean task. Computing is what it is, programming languages are what they are, and education is not going to be a driving force for changing anything in computing.

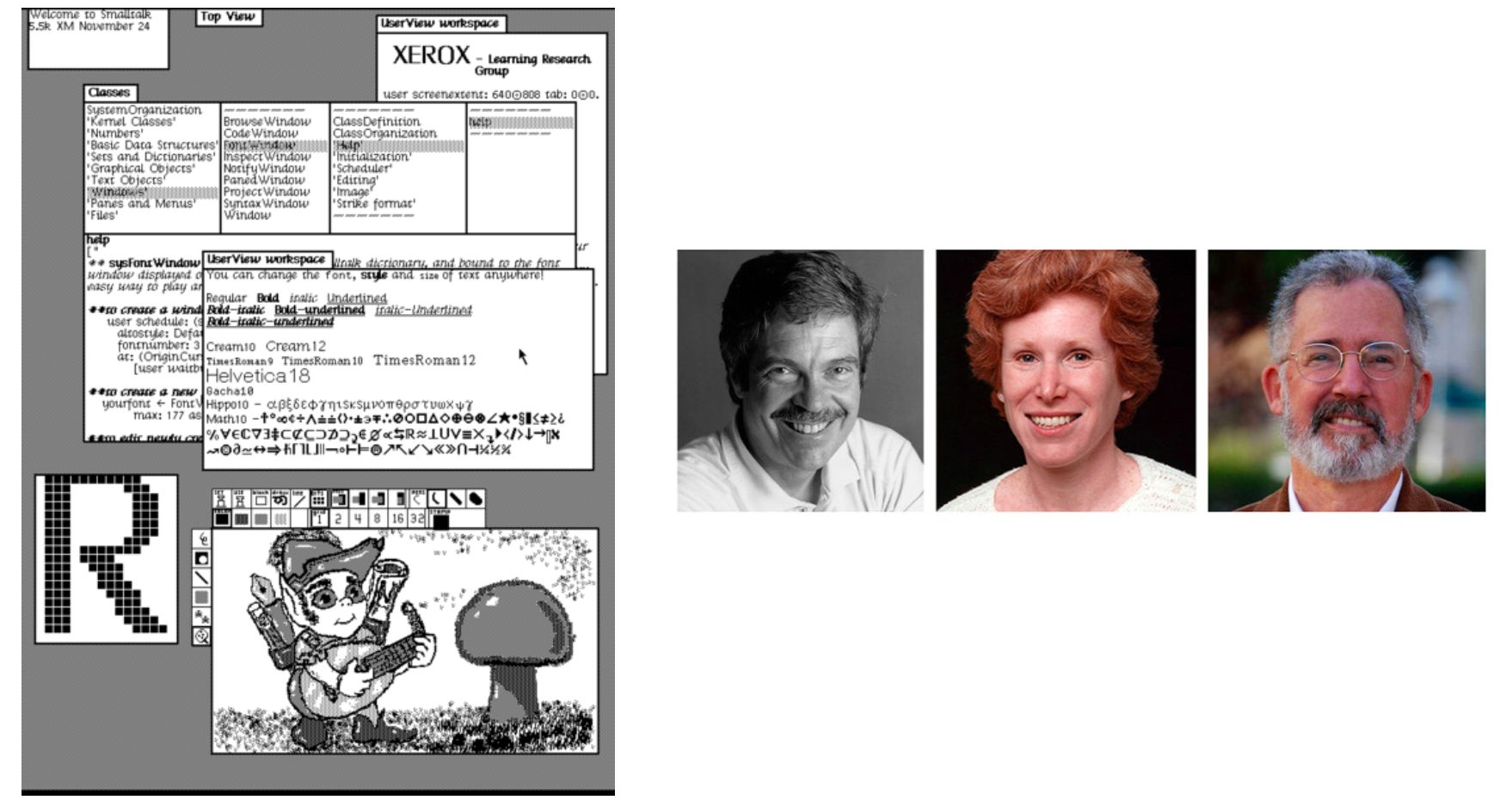

And yet, that’s exactly how the desktop user interface was invented.

Alan Kay (another Turing laureate in this story), Adele Goldberg, and Dan Ingalls led the development of Smalltalk in Xerox PARC in the 1970’s. The goal for Smalltalk was to realize Alan’s vision of a Dynabook, using the computer as a tool for learning. The WIMP (overlapping Windows, Icons, Menus, and mouse Pointer) interface was invented in order to achieve computing education goals. For the purposes of education, the user interface that you are using right now was invented.

The Smalltalk work tells us that we don’t have to accept computing as it is. Computing education today focuses mostly on preparing students to be professional software developers, using the tools of professional software development. That’s important and useful, but often eclipses other, broader goals for learning computing. The earliest goals for computing education are different from those in most of today’s computing education. We should question our goals, our tools, and our assumptions. Computing for everyone is likely going to look different than the computing we have today which has been defined for a narrow set of goals and for far fewer people than “all.”

Entry filed under: Uncategorized. Tags: computing education, computing for everyone, history, Teaspoon.

23 Comments Add your own

Leave a comment

Trackback this post | Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed

1. orcmid | November 26, 2021 at 1:12 pm

orcmid | November 26, 2021 at 1:12 pm

I confess to focusing so much on programming for software development. And I just caught myself in a beginner-mind failure. I have many of those but this one was oozing serious tacit understanding.

I recall in the day when, as my colleague Bill Burge would say, “computer science is full of people who were almost something else.” There was no barrier to entry, thankfully (especially for the ACM, which I joined originally in 1961). It dropped into my lap as a college drop-out in 1958 and I started my professional career at what was then Remington Rand Univac after seeing Grace Hopper speak at a Share meeting (IBM technical computing user group).

It was all about creativity and the love of computing for me and I had longed for the day when personal computing was achievable with personal devices, what the semiconductor advances made possible in the late 1970s.

In the earliest days, it was amazing that we could do something we loved, and people would pay us to do it. It also got to the point where it was not so much fun but requirements of others.

I remember the C.P. Snow book, and also “The New Industrial State.” We were living under a nuclear umbrella and fears about launches in mistake, governed by arrangements that had serious social considerations. We are not free of that, nor of tyranny of the technician, although the playing field seems to have changed. I remember Sputnik in the October of my freshman year and how the arms race took a turn from which we have not recovered, no matter that Mutually Assured Destruction is no longer current vocabulary.

My attention is back on making software development accessible,

although I am tending toward my long-time fascination with computer

games as a direction. I endorse “the study of computers and all the phenomena surrounding them.” I fancy some of the old-dog tools, and not certain how the route intersects teaspoon languages. It was always play. Varied toys.

2. Justin | November 26, 2021 at 2:30 pm

Justin | November 26, 2021 at 2:30 pm

The idea of Computer Science for All is especially important today because of the extent that technologies like Machine Learning and Data Science are being embedded in all the systems that govern our lives. Most of the decisions behind how to model these systems and what data is used to train them are being made by computer specialists and often only focus on technical correctness and are motivated primarily by financial/competitive advantage.

Questions about whether we are modeling the right things and whether we’re using the right data and making the right tradeoffs should belong to society at large. Historians, sociologists, psychologists, and others have knowledge and perspectives that should be taken into account. Making computer science accessible to these disciplines is important as a check on the technology that is becoming embedded in our lives.

3. orcmid | November 26, 2021 at 4:06 pm

orcmid | November 26, 2021 at 4:06 pm

I concur, @justin, although I think the net has to be wider than that, to an informed electorate and those who claim to account to them.

I was a fan of newscaster/commentator Peter Jennings. And when the Challenger explosion occurred, I saw how much he was a deer caught in the headlights around what was the event and how to understand it, all in the immediate time when none of us knew the proximate cause, only the tragedy, yet people felt compelled to conjecture.

Tom Brokaw did better, as a friend of one of the astronauts and maybe more attuned to the space program. There were others on the scene at places like JPL who also provided accurate information as it unfolded. And of course, the social heart of it and the launch-pad chicken revealed how institutions can become what they were created to conquer, as dying physicist Richard Feynman showed the kitchen science of it to all of us and an inquiring Congress.

Social scientists, computer scientists, physical scientists and engineers all deal with abstractions whether recognized as such. The fidelity of those abstractions to matters of import in our empirical reality is a condition requiring broad understanding and also vigilance.

4. OTR Links 11/27/2021 | doug — off the record | November 27, 2021 at 12:31 am

OTR Links 11/27/2021 | doug — off the record | November 27, 2021 at 12:31 am

[…] Computer Science was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: … […]

5. OTR Links 11/27/2021 | doug — off the record | November 27, 2021 at 12:31 am

OTR Links 11/27/2021 | doug — off the record | November 27, 2021 at 12:31 am

[…] Computer Science was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: … […]

6. Computer Science was supposed to be taught to everyone, and wasn’t about a job - Pentest-dB | November 27, 2021 at 11:41 am

[…] November 26, 2021 at 10:00 am […]

7. fgmart | November 27, 2021 at 4:28 pm

fgmart | November 27, 2021 at 4:28 pm

Mark, this is such a great essay – thank you so much!

I agree completely that the point of CS is to change how we think (and economic benefits are a good side effect but not the raison d’etre).

And I love the Teaspoon languages idea (and its name)!

Fred

8. Perceptions, personal reality, and mental state in dissonance is dangerous | November 28, 2021 at 12:48 am

[…] Computer Science was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: …. There is training and then there is education. This post is a bit of history and a lament that training dominates when it comes to computers. […]

9. ● NEWS ● #CER #Education ☞ #ComputerScience was always supposed to … | Dr. Roy Schestowitz (罗伊) | November 28, 2021 at 4:02 am

[…] ● NEWS ● #CER #Education ☞ #ComputerScience was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: A historical perspective https://computinged.wordpress.com/2021/11/26/computer-science-was-always-supposed-to-be-taught-to-ev… […]

10. My Week Ending 2021-11-28 | doug — off the record | November 28, 2021 at 5:00 pm

My Week Ending 2021-11-28 | doug — off the record | November 28, 2021 at 5:00 pm

[…] great post summarizing the original purpose of programming which was not all about getting a […]

11. Dorian Love | November 28, 2021 at 11:33 pm

Dorian Love | November 28, 2021 at 11:33 pm

Reblogged this on The DigiTeacher.

12. rjwprogressive | November 30, 2021 at 7:06 pm

rjwprogressive | November 30, 2021 at 7:06 pm

AN ANECDOTAL TIDBIT HERE: IN 1968 +/-, I WAS AN ENGLISH MAJOR AT A SMALL LIBERAL ARTS UNIVERSITY IN PA, MY SISTER WAS A MATH MAJOR AT A RESPECTED WOMEN’S COLLEGE. SHE STARTED WORKING AS A “SYSTEMS ENGINEER FOR IBM.” IT SOUNDED INTERESTING TO ME SO I WENT TO THE “COMPUTER PROF” TO ENQUIRE INTO LEARNING SOME COMPUTER STUFF. HE TOLD THE ONLY COURSES HE TAUGHT WERE DESIGNED FOR ENGINEERING STUDENTS AND BUSINESS MAJORS… SAD.

13. Updates from Fall Term | This is what a computer scientist looks like | December 1, 2021 at 9:11 am

Updates from Fall Term | This is what a computer scientist looks like | December 1, 2021 at 9:11 am

[…] privilege the foundations students bring into a course, but that’s a topic for another time.) Mark Guzdial’s latest blog post about the history of computing education echoes (and much more clearly articulates) some of the […]

14. Computer Science was always supposed to be taught to everyone, and it wasn’t about getting a job: A historical perspective – Carla’s Blog | December 1, 2021 at 1:45 pm

[…] adapted by computer research blog […]

15. Mark Miller | December 1, 2021 at 7:40 pm

Mark Miller | December 1, 2021 at 7:40 pm

Thank you for this wonderful post, Mark. I am giving a talk tomorrow which espouses many of the same ideas — I will be citing this blog.

16. JOHN BAHO | December 2, 2021 at 12:47 pm

JOHN BAHO | December 2, 2021 at 12:47 pm

Absolutely beautiful article. Loved it. Saw

17. Harris McClamroch | December 2, 2021 at 2:45 pm

Harris McClamroch | December 2, 2021 at 2:45 pm

When CS in LSA and Computer Engineering were combined in 1968 into the grad CICE program, the idea was to integrate computing, information, and control into a new, unified academic program. It was very successful in bringing a broader perspective to computing until it was disbanded in mid 1980s.

18. Mayowa | December 3, 2021 at 11:55 am

Mayowa | December 3, 2021 at 11:55 am

Great post! I will start learning computer from a different perspective going forward.

19. garystager | December 5, 2021 at 5:21 pm

garystager | December 5, 2021 at 5:21 pm

Nicely done Mark! Now I have a lot more to read!

Have you seen our new book? http://cmkpress.com/20things

Hope you are safe and well,

Gary

>

20. Tom Morley | December 11, 2021 at 6:23 pm

Tom Morley | December 11, 2021 at 6:23 pm

C. P Snow makes a good point. Why is is OK in educated society to claim ignorance and disinterest in Mathematics, but not OK to claim illiteracy?

21. Updates: Developing the University of Michigan LSA Program in Computation for the Arts and Science | Computing Education Research Blog | February 22, 2022 at 7:00 am

Updates: Developing the University of Michigan LSA Program in Computation for the Arts and Science | Computing Education Research Blog | February 22, 2022 at 7:00 am

[…] figure out what LSA was doing in computing education, and what else was needed. Back in November, I talked here about the three themes that we identified as computing education in […]

22. Three types of computing education research: for CS, for CS but not professionally, and for everyone | Computing Education Research Blog | May 25, 2022 at 7:00 am

Three types of computing education research: for CS, for CS but not professionally, and for everyone | Computing Education Research Blog | May 25, 2022 at 7:00 am

[…] My research is one level further out. I’m interested in studying what should we be teaching to everyone, whether or not they’re going to program like professionals, and how do we facilitate that learning. These students might not use the same tools or languages, and certainly have different goals for studying computing. I offer three reasons for the broader “everyone” to learn computing (drawn from the work of C.P. Snow, Alan Perlis, Peter Naur, and Seymour Papert — see this earlier blog post): […]

23. Broadening Participation in Computing by Moving Away from Computer Science: Information, Arts, Humanities, and Sciences offer better models for #CSforAll | Computing Ed Research - Guzdial's Take | June 15, 2023 at 8:01 am

Broadening Participation in Computing by Moving Away from Computer Science: Information, Arts, Humanities, and Sciences offer better models for #CSforAll | Computing Ed Research - Guzdial's Take | June 15, 2023 at 8:01 am

[…] and touching on many different aspects of modern life. (I tell the story of those early definitions in this blog post.) More modern computer science definitions are much more […]